Source: Omaha World Herald, by Barbara Soderlin

A large new pork processing plant set to open next month 100 miles north of Omaha is expected to add more fuel to the Nebraska pork industry’s recent growth spurt.

The plant in Sioux City, Iowa, will give Nebraska farmers another buyer for their growing numbers of hogs. And it could drive them to build more hog barns on their farms in eastern Nebraska, in hopes of adding income that’s hard to come by today through row crop farming.

The plant, run by Seaboard Triumph Foods, is one of five opening around the Midwest, adding a total of about 10 percent more processing capacity for the industry. The growth may not lead any existing plants to close, though, because U.S. hog numbers are expected to keep growing fast enough to keep the plants productive, observers said.

But there’s a cloud threatening to rain on the industry’s growth parade: the risk that the upheaval in free trade deals under President Donald Trump will dampen other countries’ demand for U.S. pork. The industry is counting on those export sales for continued expansion.

“The reason that (the industry is) profitable right now, despite an increase in production, is that exports are surging,” said Dermot Hayes, ag economist at Iowa State University in Ames.

That could change: Trump in January pulled the U.S. out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free trade agreement with nations including Japan, which is the biggest buyer of U.S. pork by value. The deal would have improved the U.S. pork industry’s terms of access to the market.

Then, in June, Japan and the European Union reached agreement on their own free trade deal. The European Union is the United States’ biggest competitor when it comes to selling pork to Japan, and the deal now puts the United States at some disadvantage.

“It’s disappointing to lose a potential new market; it’s scary to lose an existing market,” Hayes said.

The industry will try to influence the Trump administration to improve the United States’ own trade standing with Japan before the EU deal takes effect next year.

“It’s pretty imperative that we get the same deal done in the meantime,” said Steve Meyer, pork industry analyst for Indiana-based Express Markets Inc. Analytics.

It’s also important for the industry not to lose ground with Mexico and Canada, among its top four export partners, when negotiations begin this week over the North American Free Trade Agreement, said Al Juhnke, executive director of the Nebraska Pork Producers Association. “We don’t want to mess that up,” he said.

One of the owners of the Sioux City plant said he is watching the Trump administration’s trade moves.

“We’re going to have more volume, and we’ve got to figure that out, to move that product,” said Glenn Stolt, chief executive officer of Minnesota-based Christensen Farms. Christensen is a large family-owned pork producer with operations in five states, including a growing footprint in northeast Nebraska.

But Stolt said he’s optimistic because of the need to feed the world’s growing population, and because Christensen Farms has established customers and presents what he sees as a compelling marketing message as a farmer-owned pork producer.

Christensen Farms is a part owner of Missouri pork processor Triumph Foods, which will co-own the Sioux City plant in a joint venture with Kansas-based Seaboard Foods.

The plant will process 10,500 hogs a day at first, making it about the same size as each of the three large pork processing plants operating in Nebraska today: the Hormel plant in Fremont, Smithfield Foods’ Farmland plant in Crete, and Tyson Foods’ plant in Madison, according to research by Meyer published in July in National Hog Farmer.

But by the end of 2018, the new Sioux City plant is expected to double in capacity to 21,000 hogs a day, putting it among the six largest pork slaughterhouses in the country.

The plant is on track to begin commercial operations Sept. 5, and is now hiring to meet a target of 1,100 employees, with wages starting at $15.25 an hour, said Mark Porter, chief operating officer for Seaboard Triumph Foods.

The opening of the five new plants around the Midwest — two in Iowa, and others in Michigan, Missouri and Minnesota — comes after more than a decade of no major new plant expansion in the country, Porter said.

Seaboard Triumph will source about two-thirds of its hogs from its owners, but it will be buying the other third on the market from other producers in the Sioux City region.

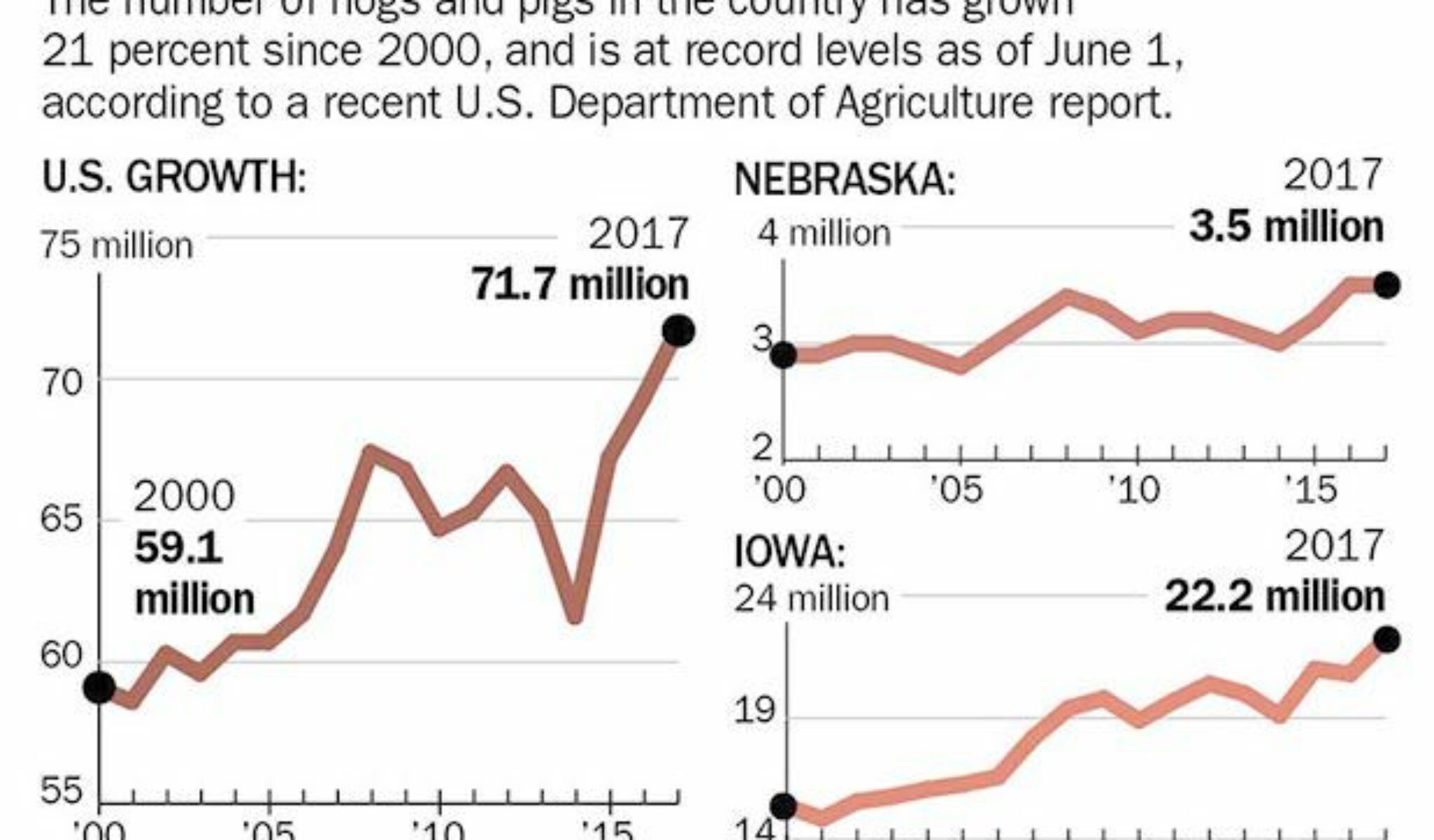

That could drive even more growth in hog numbers in Nebraska. After 15 years of essentially stagnant numbers here, Nebraska added about 16 percent more hogs and pigs in the past three years.

The growth comes in part because of a 2016 state law ending a ban on meatpackers’ ownership of hogs in Nebraska, Juhnke said.

“People around the country look to Nebraska now and they really say ‘Hey, that state is definitely open for business again in the swine industry,” Juhnke said.

Nebraska’s pork industry still plays second fiddle to its cattle industry. There are nearly twice as many cattle in Nebraska as hogs and pigs. And it doesn’t come close to the amount of pork in neighboring Iowa, which leads the nation in the number of hogs it raises and slaughters, and is also in a growth phase.

The growth in Nebraska is hard to notice from the highway. Unlike cattle, which graze outdoors and are fattened in outdoor feedlots, pigs typically are raised indoors in barns, where access is tightly controlled to prevent disease outbreaks.

Juhnke sees more growth on the horizon and says that means economic development for Nebraska.

“There’s a whole industry that would like to see as many barns as possible out there,” he said.